env entry 8- link to class presentation

“Quit thinking about decent land-use as solely an economic problem. Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” –Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There, 1949.

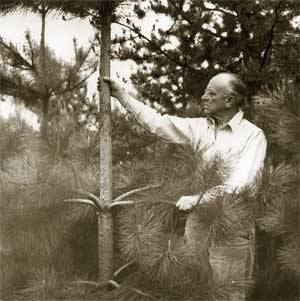

(Fig. 4. Leopold’s Land Ethic. Google images, public domain.)

According to Aldo Leopold, philosopher and scientist, the purpose of an ethic is to evolve and limit modes of communication between individuals, groups, and societies. An individual competes for his/her place in those communities and is simultaneously driven to cooperate with others by his/her ethic (VanDeVeer, p215-216). Aldo Leopold’s environmental ethic, or “land ethic”, aims to expand the boundaries of the currently dominant anthropocentric ethic to include all collective elements of the land (animals, plants, waters, soils, organisms etc.) Leopold’s ethic is in accordance with the idea of Environmental Citizenship, which is defined by the Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy as “the idea that each of us is an integral part of a larger ecosystem and that our future depends on each of us embracing the challenge and acting responsibly and positively toward our environment” (Hargrove, 323). It is similar to the modern idea of Environmental Stewardship, but stewardship carries a religious connotation and has ties to Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. With citizenship, moral standing of all life is not dependent on divine origin or command (see Fig. 4). Under this land ethic, the role of humans in the environment is no longer domination/dominion as “stewards” implies, but instead humans now have the role of “citizens” whom respect, live with, and depend on the land in a secular sense.

(Fig. 5. Leopold’s Land Pyramid. Google images, public domain.)

During his life, Leopold fought against overhunting leading to species and wilderness degradation with no concern for the environment in which everything exists and on which everything depends. Leopold is credited with creating the term “wilderness”, when there was a want for a term to describe all land which he considered an “arena for a healthy biotic community” (VanDeVeer, p216). He expresses this interdependent community through “The Land Pyramid”, is the biotic pyramid portrayed in ecology (see Fig. 5). Upward cycling of energy flows from the abiotic elements of the earth at the base through the trophic levels, omnivores, and carnivores, gradually decreasing in numerical abundance. But this pyramid does not represent a hierarchy of moral standing, it is organized by what is consumed (energy, food) and what is consumer through lines of dependency. One of the most important elements is that the Land Pyramid is not a closed circuit, and there is downward cycling of energy of decomposition of the apex layers which decay and dissipate into the ear, soils, and wilderness in general to sustain the circuit and allow for upward cycling. This cycle, undisturbed, is able to regenerate to sustain itself.

(Fig. 6. “Running on Empty”. Google images, public domain)

Enter humans and the “Anthropocene” epoch, which saw the invention and development of agriculture and tools. With homo sapiens came and disrupted the pyramid with agricultural control, the base of the pyramid became unstable, which has led to mass extinctions from insects to apex predators. This phenomenon of unsustainable ecosystem degradation for the sake of human goods and services increases human populations beyond the earth’s maximum carrying capacity, which also means that resources and animals are disappearing so rapidly that they cannot regenerate through upcycling and down cycling of energy. This is seen not only in animals, but in other resources on earth that Leopold includes in his ethic, such as water and fuels (Fig. 6). Today’s ethics that inform laws and regulations regarding how humans should use and live on the land are almost entirely driven by economic self- interest. Leopold adds that when environmental conservation policies are enacted, it is because of economic evidence of potential market losses associated with environmental abuse/neglect or gains with proper care, not because of a disruption in the symbiosis of the wilderness. Without the entire Land Pyramid being considered, even the policies in place might only be short-term fixes for the sake of the market, as opposed to long term fixes for the sake of the biosphere.

(Fig. 7. “Maryland Crab Feast”. Google images, public domain)

An example of this is the recent crisis which has been occurring within the Maryland Blue Crab population of the Chesapeake Bay, as described by a report released by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) in 2008. The report claimed that the crab population in the bay has been dropping by the millions over the last decade as a result of several factors all caused by human interference: nitrogen and phosphorus pollution destroying the crabs’ habitat and wiping out the crab’s food (clams and worms); Overfishing the population that remains; poor regulation of bay cleanliness and maintenance. I grew up in Baltimore, and the culture of boiling dozens of Maryland Blue Crabs, covering them in Old Bay spice, and then inviting over the entire neighborhood/family for a feast or football came was a common occurrence (Fig. 7). Crabs became more and more expensive as their numbers decreased, and eventually the government had to put a ban on the commercial harvest. Human behavior was damaging multiple elements of the Land pyramid which effected the crab’s habitat, and the study shows that the government only interfered because of the market crisis that eliminated thousands of crab related jobs (see Fig. 8) and decreased the value of a prominent Maryland market (see Fig. 9). This is exactly the problem that Leopold describes and attempts to change with a land ethic.

(Fig. 8. Job Loss. Google images, public domain)

(Fig. 9. Crab Market Decrease. Google images, public domain)

A major flaw with Environmental Citizenship and the Land Ethic is that it cannot be reduced to a set of universal principles because conditions that are necessary for symbiosis vary by location and culture. Cultural appreciation of animals can be useful however, as it is the practice of humans finding value in animals beyond their utility (as symbols, metaphors, representative of values etc.) This appreciation has lost popularity with the quick growth of the global market, but Leopold thinks that it could be the key to the incorporation of his Land Ethic and give the wilderness moral standing. He says that: “Wildlife once fed us and shaped our culture. It still yields us pleasure for leisure hours, but we try to reap that pleasure by modern machinery and thus destroy part of its value. Reaping it by modern mentality would yield not only pleasure, but wisdom as well” (Leopold, p187).

Word count: 1227

Two-line discussion question: Can Environmental Citizenship secularizes Environmental Stewardship. Are the two in direct conflict, or can conservation and sustainability be achieved even through the consideration of both?

Citations:

Hargrove, Eugene C. “Environmental Citizenship”. Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy.

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac: With Other Essays on Conservation from Round River (Galaxy Books) (p. 187). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. 1949.

Lipcius, Dr. Romuald N. “Bad Water and the Decline of Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay”. Report: Saving a National Treasure. Chesapeake Bay Foundation. 2008.

VanDeVeer, Donald, Pierce, Christine. The Environmental Ethics and Policy Book, 3rdedition. Thompson & Wadsworth. 2003.

Leave a comment